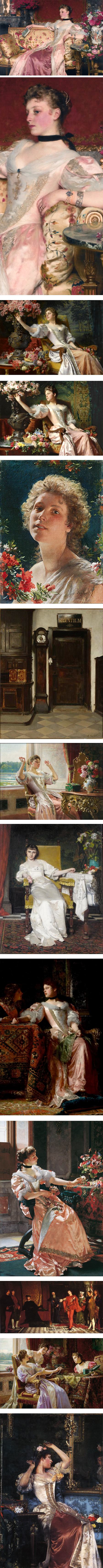

Pomegranates and Other Fruit in a Landscape, Abraham Brueghel

In the Metropolitan Museum of Art; use the download or zoom links under their image.

This 17th century still life is an example of how tenuous the attribution of historic art can be. Over time, it has been ascribed to Diego Velázquez, Giuseppe Ruoppoli, and Giovanni Paolo Spadino.

The current attribution is to Flemish painter Abraham Brueghel (son of Jan Brueghel the Younger, grandson of Jan Brueghel the Elder and great Grandson of Pieter Brueghel the Elder, quite a family heritage).

Still life set against a landscape is not an unusual compositional device in painting, but this one looks wonderfully strange. If you take the background shapes to be mountains, the three fruits in the background are atop and escarpment, and those in the right foreground seem to hang above a waterfall.

Whether still life at a giant scale is actually the artists intention, I don’t know, but I enjoy being able to interpret it that way. I also like the tiny (and/or giant) lizard in the foreground.

Regardless of illusions of scale — intended or imagined on my part — it’s a beautiful still life.

It’s naturalistic at a distance, but I love how brushy and painterly this is in close-up — wonderful for a 17th century still life — the apples, figs and grapes look as though they might have come off the brush of Manet, 200 year later.