In the 1970’s the scope of style in American mainstream comic book art was suddenly expanded by the “Phillipine Invasion”, the advent of a number of highly skilled Filipino comics artists establishing themselves with the American comic book publishers.

These artists, already established in the Philippines’ active comic book market, owed as much to the influence of Golden Age pen and ink illustration and early 20th century American newspaper comics as they did to the contemporary comic book styles of the time, and they had a distinct impact on the styles of many American artists.

Many of them became well known, like Alfredo Alcala, Ernie Chan, Tony DeZuniga, Rudy Nebres, Francisco Reyes and Alex Niño, among others.

My favorite from this group of artists — and one of my favorite comic book artists in general — was Nestor Redondo.

Redondo first came to my attention when he was drawing short stories for DC Comics’ anthology horror titles like House of Mystery. He then did a knock-out run on six issues of Rima, The Jungle Girl, bringing to the title a flair reminiscent of the 1930’s newspaper adventure strip Jungle Jim by the great Alex Raymond.

Redondo really knocked my socks off, though, by doing the impossible — following up on Bernie Wrightson’s landmark run on the first ten issues of Swamp Thing; not only maintaining the extraordinary standard Wrightson had set, but bringing his own sensibility to the series and hitting it out of the park for thirteen more issues.

In addition to his numerous projects for the Philippine comics market and several other projects for the American publishers, Redondo also brought his solid but fluid inking style to collaborations with other artists, notably on one of my favorite lost gems of 1980’s comics, Doug Moench’s Aztec Ace.

I’ve long thought Redondo’s comics work and pen and ink illustration worthy of a collection, and though it has been a long time coming, we finally have one courtesy of the always remarkable Auad Publishing, who also published a collection of the work of Alex Niño (unfortunately, sold out). Auad was kind enough to provide me with a review copy of the new book on Redondo’s work.

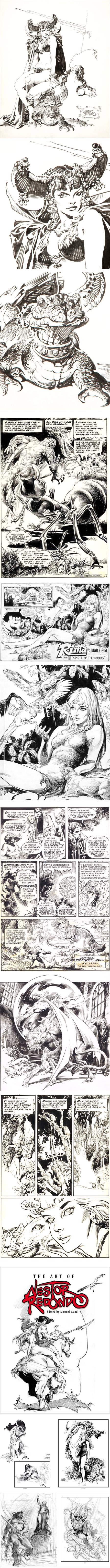

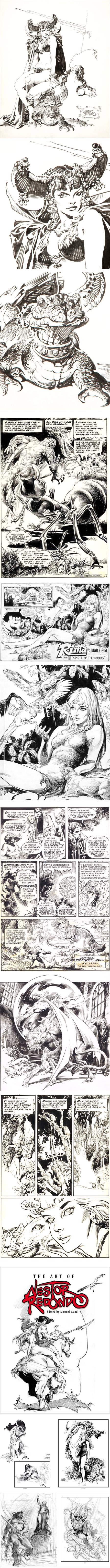

The Art of Nestor Redondo (images above, top, with details, and bottom three rows) collects a variety of the artist’s comics art, ink drawings, splash pages, sketches and pencil drawings in an inexpensive, but high quality, 80 page black and white volume.

It’s paperback with nicely stiff card covers and high quality paper; and the printing is beautifully sharp and crisp, showing the details in Redondo’s ink drawings to best advantage. Most of the art was scanned from the original drawings.

The book is available directly from Auad for $24 USD. If you click on the cover in the listing on the Auad site, you will get a pop-up preview gallery of images from the book. Auad is a small publisher, and most of their past titles are sold out. If you want a copy of this one, you should probably order it sooner rather than later.

For those who aren’t familiar with Nestor Redondo, it’s a nice introduction to his style and abilities; for those who are already fans of Redondo, it is, of course, a must-have.

For me, the primary appeal of Nestor Redondo’s style is in his solid draftsmanship, the careful balance between areas of detailed hatching and open white space, and the key element of strategic openness in his line work. Unlike many artists who try too hard to lavish detail on their ink drawings, Redondo knew how to leave his outlines open in just the right places to let his figures breathe.